The Percy French song ‘Are you right there, Michael, are you right?’ is well-known but how many know the story of the railway or the court case which led to the composing of this song.

The famous West Clare Railway was a railway system formed by the co-operation of two companies, the West Clare and the South Clare Railways, and ran together as private railways from 1892 until 1923 when they were amalgamated by the new State under the control of the Great Southern Railway. It continued to run until closed under CIE ownership in 1961. It ran a 48-mile route from the county town of Ennis to Kilkee with a 5-mile branch line to the port of Kilrush and the pier at Cappa on the Shannon Estuary.

Its Main Reason for Being Built.

All of the proposals for railways to be built in west Clare (and there were many) were for a line to link Kilrush and Cappa with Kilkee and, throughout its existence, the main destination of the line was Kilkee. In the 1840’s when the first proposal was made, the Shannon Estuary was the main area of British steam-boat operation – a new invention introduced in the 1830’s. The passenger traffic by steam-boat from Limerick or Foynes to Cappa for a “Society” holiday or day excursion to Kilkee was vast by the standards of the day and the railway, when built, made full use of the trade.

Therefore, when opened for traffic by its owners, (the South Clare Railway Company), in 1892, the station at Kilkee was the prime showpiece. An elegant building (still to be seen largely unaltered) containing the railway’s functions and full facilities for its passengers, the station was, however, on the edge of the town giving rise to considerable horse-drawn taxi trade to take travelers into town and their accommodation.

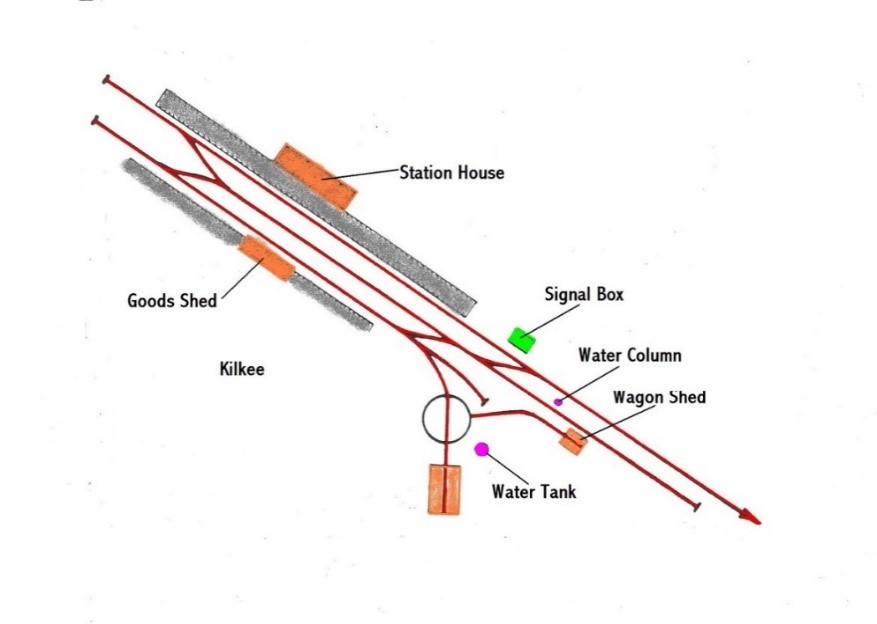

Kilkee Station – Track layout schematic. Not to scale

Upper Class Travellers to Kilkee

In the somewhat pointless lives of leisure that these “Society” travellers led, it was important to be known to do the “right” things and one of these was to invite the “right” people for afternoon tea and the like. In order to do this (and to avoid the gaffe of failing to give an appropriate invitation) it was important to know who was “in town” at the time.

This was best done by being at the station when people arrived and, since turnaround day was a Saturday, the “Great and Good” would be seen parading and promenading in their finery around the station waiting to welcome the evening train and watching for whoever was arriving for their holiday.

Mixed in amongst the gentry would be found dozens of local farmers with their pony or donkey traps offering to taxi travellers and their mountains of luggage to their houses, hotels or lodgings. Also, large numbers of local lads were there similarly offering to carry luggage in exchange for a substantial tip.

One can only wonder at the hustle and bustle of the station and its precincts on a Saturday evening as this ritual was performed.

Hanky-Panky on the Edge of Town.

Being at the edge of the town, the station would be very quiet at night. Empty carriages left unattended can bring their own dangers not least in matters of morality. Designed to be comfortable, warm and dry for the passenger, coaches left in the dark and quiet of an unattended station yard at night will soon attract an appreciative clientele if possible.

The railway’s Company Secretary received a letter on 13th June 1894 signed by one John Mescall of Kilrush stating that incidents of courting couples using unattended carriages at Kilkee at night for their nefarious purposes were widespread and that the parish priest had referred to such incidents at Mass accordingly. Keen to protect the Company’s good name, the Secretary began an investigation forthwith.

No evidence of such goings-on was discovered, however, and things became even worse when Fr. Quinliven, Kilkee’s parish priest, denied making any such references. Furthermore, the letter writer’s name proved to be false as no-one of that name or even the address was known in Kilrush.

It was decided that the letter was a hoax and the inquiry was concluded. It was assumed that the letter had been written by a former employee at Kilkee Station who had been dismissed the previous year for abusing the station agent while under the influence of drink.

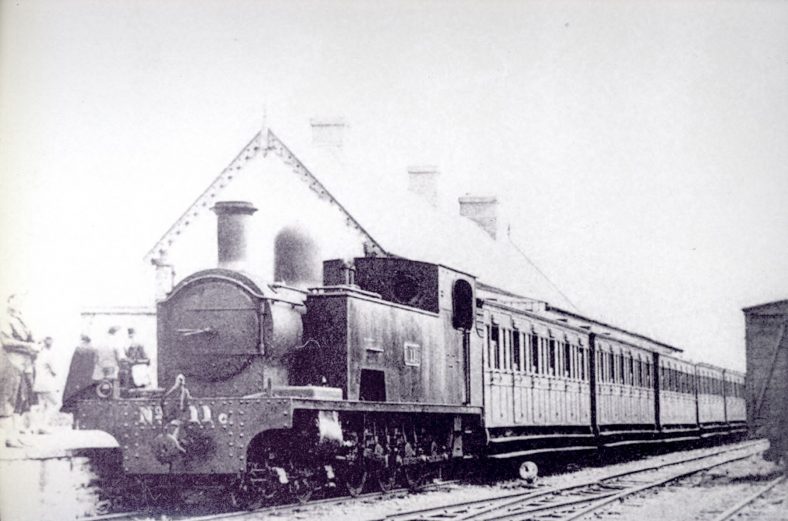

Kilkee station panorama

Percy French and the Song That Made The Railway Famous

The fame of the West Clare Railway emanates from the song, “Are ye Right, There, Michael?” written by Percy French about the railway following a particularly unfortunate experience he had on a journey made on Monday 10th August 1896 as a result of which he arrived to give what he called his “Society Entertainment” at Moore’s Hotel, Kilkee, some 5 hours late.

In the song, French describes the railway as the typical, bumbling fiasco of an Irish country railway beloved by Hollywood and “Paddywhackerers” the World over. He mentions the stations by name and just about every possibility of things that can go wrong go wrong on this imaginary excursion.

French was a regular traveler on the railway and came to know it and its foibles well as Kilkee was one of his favourite watering holes. Of Moore’s Hotel, he wrote

“At Moore’s Hotel they do you well for 1/6d a day.

With Nolan’s lambs and Lipton’s hams and Mazzawattee tay”

Oh! For such gracious living!

The Railway’s Performance.

Although carrying 250.000 passengers a year in its heyday along with 40.000 tons of freight, 40.000 livestock animals and 8000 tons of hand-cut turf from the bog at Shragh, sadly French’s description of the line’s performance was, although extreme, not too far from the truth. The financial provisions of the “Tramway’s Act 1883” under which the railway came to be built had the effect of preventing the Directors from amassing the capital sums needed to run an efficient business and the land and its economy was just not big enough to support the costs of providing the facility. The line and its stock were built on the cheap. The maintenance routines were inadequate. Unfortunately, the abilities of many of the directors and managers were poor.

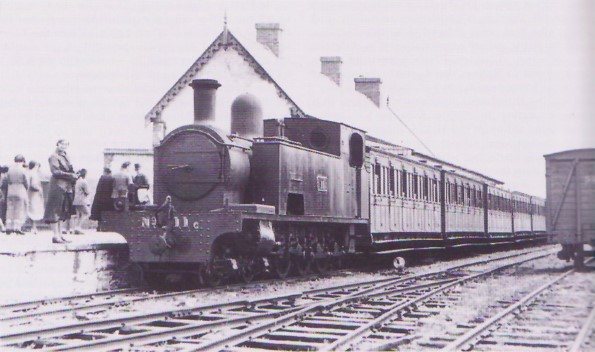

Two trains in Kilkee station

Consequently, the engines were run for too long after maintenance had become an issue. The trains were often over-loaded and the engines needed to be thrashed to get them over the summit levels thereby exacerbating the maintenance problem. Trains were chronically and regularly late. They became uncomfortable and dilapidated and passenger numbers fell drastically over the years.

Farmers became infuriated by the railway’s inability to provide an adequate number of wagons to carry their livestock and many would walk their cattle to Ennis Fair rather than try to use the railway. This deterred the better cattle traders from coming to the area.

From 1916 onwards, even the Shannon estuary steamer excursion services were stopped when German U-Boats were reported to be operating in the river mouth. It is a major tribute to the dedication of the staff that the railway ran at all.

Film Stars.

In 1956, just after the last steam engines had been withdrawn in favour of the new diesel-powered machines introduced to improve the line’s performance, the celebrated Hollywood film director, John Ford, came back to Ireland (from where his forefathers had emigrated) to film a series of three short plays grouped together under the title, “Three Leaves of Shamrock”, for Warner Bros.

Tyrone Power introduced and linked the plays which were performed by actors of the Abbey Theatre, Dublin, – all well-known personalities of the day. They were all filmed at locations in Co Clare or Galway City and, for the second play, “A Minutes Wait”, Kilkee Station was chosen as the set and re-named “Dunfaill”.

Engine number 5 (the oldest engine of the railway) was resurrected from the scrapyard at Inchicore, re-painted, brought back to steam and transported back to the line it had served throughout its existence along with two coaches and a guard’s van.

A considerable number of local people were employed as extras in the film which depicted a harassed Station Master whose wish to get the train away on time is thwarted at every stage by some very “Hollywood” Irish reason or circumstance.

The film is a superb record of the West Clare Railway operating in its steam days and contains some stunning landscape scenes of the countryside just outside Kilkee at the north shore of Poulnasherry Bay.

Closure.

Despite all its short-comings, the WCR became a well-loved institution in the area it served and when, in 1960, CIE (its owners) announced that the line was losing £23.000 a year and could no longer be supported, a howl of protest was raised. Shopkeepers refused to accept loads delivered by road in protest and a deputation went to Dublin to present their case to the Minister.

After having had their say, the Minister stated that he would consider their points very closely in his deliberations and said that he was so moved by their efforts that he would endorse their tickets so that they could travel home First Class. No-one could produce a ticket as all had travelled by road. Embarrassed, they looked at the Minister who shrugged apologetically and said, “What else can I do but close the line?” There was no answer.

Kilkee station panorama

The last train ran on 31st January 1961 and was not the timetabled train advertised because CIE had cancelled that service without notice in fear of theft of equipment and demonstrations against closure. The following day, teams of workmen moved in at Kilrush and Kilkee to lift the track which was collected together at Ennis and eventually sold to Nigeria for re-building there at a price of (surprise/surprise) £23.000. Sadly, a terrible civil war (the Biafran War) broke out as the track was delivered on the port quayside and, to anybody’s knowledge, was abandoned and left to rot.

Resurrection.

However, this was not the end of the West Clare Railway. In 1985 when the station at Moyasta came on the market for sale, a group of local businessmen purchased the property and, with the help of the Rural Resources and Development Organisation and “Leader” funding, created an Interpretation Centre in memory of the railway. The engine No 5 was brought back to Moyasta from its plinth outside Ennis Station and was restored to be found today just 5 miles from Kilkee on the coast road (now called the “Wild Atlantic Way”) in full steam and carrying passengers again.

It is hoped that the line to Kilkee will be re-laid in conjunction with the County Council’s plans to open the whole track bed of the railway as a “Green Way” open for the general public’s recreation whether on foot, bicycle or pony.

See this link for a very short video of the West Clare railway.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page